5 amazing planetary nebulae: how to find the hourglass, the ring of smoke and the snowball

What are planetary nebulae? How can I observe them? Let's take a trip to the 5 most beautiful objects for your telescope.

The Dumbbell Nebula M27 in constellation Vulpecula. Photo: Marcus Schenk

The Dumbbell Nebula M27 in constellation Vulpecula. Photo: Marcus Schenk"Hmm, a nebula."

This comment was made recently by someone looking through my telescope. There are people who are not especially enthusiastic when they first take a look through a telescope.

Why is that?

Because they don't know what they're looking at. It's important to know the background to an object. What exactly it is that we are observing.

When I explained it to him, his response was "Wow!" Observing is simply a lot more fun when you have some background information.

In this article I will introduce you to 5 interesting planetary nebulae, together with a guide to locating them.

But first of all, let's briefly find out what is behind these mysterious objects.

What are planetary nebulae?

Planetary nebulae are deep sky objects that lie far outside our solar system at a distance of many light years. These nebulae were originally stars, just like our Sun.

Just like the lives of us humans, stars are born, experience a childhood, adulthood and old age. Of course, they are not living organisms in that sense, but they do undergo a transformation. However, these processes take millions and billions of years.

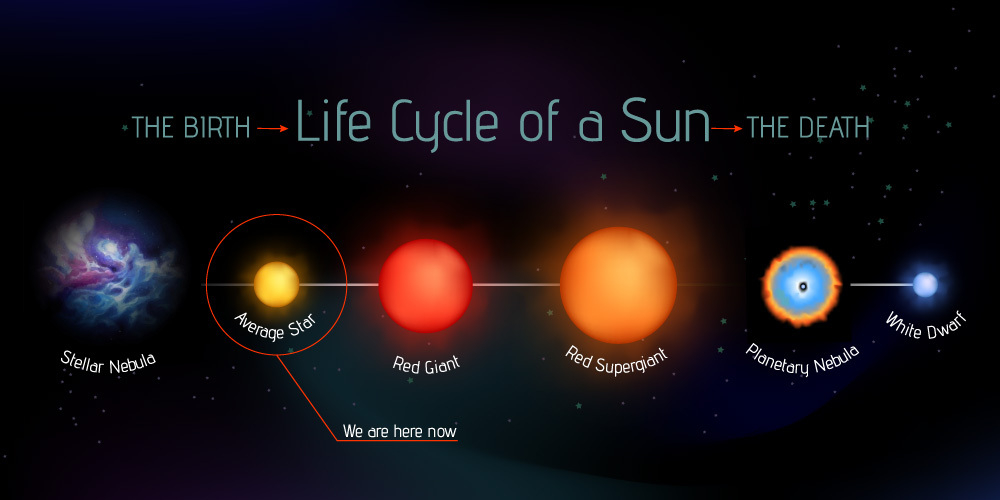

Planetary nebulae with their central stars were once red giants. Stars that expand at the end of their lives as all the hydrogen in the core is burned to helium, whilst the outer layer grows. Due to the lack of radiation pressure from within, they contract, repeatedly releasing mass and finally ended up as white dwarfs - no larger than a planet.

This is what the life cycle of a star of up to 1.5 solar masses looks like.

This is what the life cycle of a star of up to 1.5 solar masses looks like. These dying stars are formed from stars up to 1.5 solar masses, and later reach surface temperatures of around 30,000 - 150,000 K. The nebula that is thrown off consists of hydrogen, helium, oxygen and often expands at 25 kilometres per second. We can see it because hard ultraviolet radiation from the white dwarf causes the nebula to glow. By spectroscopically examining the nebula around this dead star, astronomers can discover interesting facts about the life and composition of the former star.

By the way, the origin of the term "planetary nebula" goes back to the 18th century. For when Wilhelm Herschel observed the first planetary nebulae in around 1764, they looked like the big planets of our solar system to him. In fact, this assumption based on visual observation was understandable, because telescopes at the time often had low resolution. This is how their wonderful-sounding name came about.

Clouds of smoke from ancient times

Like everything in the universe, planetary nebulae come in many different ages. Young versions may only be 2,000 years old, which we experience as compact, bright nebulae. The very oldest among them can reach 10,000 years of age, in which case they are very widely spread out and can only be seen under a dark sky. As the nebula, that once left the star, is constantly expanding, at some point it becomes invisible and loses itself in the expanse of space.

Observing Planetary Nebula

Some say that nebula objects can only be observed under a dark sky. But for some of the compact planetary nebulae, this rule actually doesn't apply. We can even observe some from the city, or at least from sites that offer only a moderately good sky.

If you think one planetary nebula looks much the same as another - this is actually far from the truth. They can take different forms, and they are clearly distinguishable from one another.

Among them there are:

- rings

- discs

- dumbbell or hourglass shapes

- irregular shapes

It’s great to be able to recognise the various forms directly while observing. In the case of the larger nebulae, it is fascinating to observe the OIII line of double-ionized oxygen with an OIII filter. If you use a larger telescope with an aperture of 200 mm or more, such a filter can be useful.

With compact nebulae, you don’t usually need a filter, instead you can simply use much higher magnification. With bright nebulae, a good sky is not so important for finding the object.

For planetary nebulae, the OIII line is a highlight with or without contrast enhancement. It shines in the green area of visible light (at 495 and 500 nanometres) and this is exactly where our eye is most sensitive. We therefore see a greenish colour with some nebulae.

1. M27 - the green beacon in space

There are just four planetary nebulae in the Messier catalogue. One of them is the Dumbbell Nebula, M27, which is also one of the brightest of its kind in the sky. It was discovered by Charles Messier in 1764, and was first described by John Herschel as a dumbbell shape.

When we look at the Dumbbell Nebula, we immediately recognise its dumbbell or hourglass shape. But that only accounts for the brightest part of the nebula, because on long-exposure images we can also make out another round nebulous halo that surrounds the hourglass.

The Dumbbell Nebula, photo: Carlos Malagón

The Dumbbell Nebula, photo: Carlos MalagónM 27 is rather large at around 3 light-years across, and is about 9,000 years old. Seen through a telescope, its greenish colour predominates, and we can make out the mag 13.5 bright central star through an 8" telescope. The two dome-like arches or ears on the right and left of the hourglass can also be seen through smaller telescopes from a magnification of around 50x upwards.

For our observation, good 10x50 medium-sized binoculars or large 20x80 binoculars are sufficient. However, observing is better and easier with a small telescope from 4” or a medium telescope of 6” or larger. Of course, there are no upper limits: completely different details can be seen through a 12" telescope.

In autumn, you need to start your observation early. The summer constellations soon sink towards the horizon, but despite this, we want to catch sight of the Dumbbell Nebula. It is hidden in the constellation Vulpecula, which beginners often miss, because it’s so small and consists of just two bright stars. You will discover it between the constellations of Cygnus and Aquila. Is M27 this easy to find? Not quite!

For this we need the constellation of Sagitta. You will find this compact constellation next to Vulpecula in the direction of Aquila. Sagitta is small but distinctive with its arrow shape.

Look for the outermost star of the arrow tip in your finderscope. Then move parallel around one degree in the direction of constellation Cygnus. Finally, follow a small arc of three mag 6.5 - 7.1 bright stars, and you will automatically arrive at the Dumbbell Nebula.

Locating chart for the Dumbbell Nebula, Stellarium

Locating chart for the Dumbbell Nebula, StellariumTwo useful observation techniques

You’re finding it difficult to see an object? These tips can help:

The filter blinking technique: Use an OIII and/or a UHC filter and place it in a filter wheel. Observe alternately and quickly with and without the filter, you'll notice the nebula as a flicker in the eyepiece.

Field sweeping: Move the telescope a little back and forth so that the stars in the eyepiece move. Now the faint nebula can suddenly appear. This is because we perceive objects in motion more clearly.

2. M57 - the delicate ring of smoke

The Ring Nebula, M57, is a summer object and is one of the most well-known planetary nebulae. Like a sightseeing tour, it is one of the highlights that you have to see, and that you will always want to re-visit.

The Ring Nebula was discovered in 1779 by the astronomer Antonie de Darquier de Pellepoix. A short while later, Charles Messier included it in his famous Messier Catalogue, a directory of relatively bright nebulae and galaxies that is an indispensable guide for amateur astronomers. In those days, they were puzzling about the true nature of the nebula. It was initially believed to be a star cluster.

The beautiful Ring Nebula, image: Carlos Malagón

The beautiful Ring Nebula, image: Carlos MalagónIn reality, the object was once a star like our Sun, expanding and becoming a white dwarf. Strong stellar winds blew and formed the Ring Nebula around 20,000 years ago. It is slightly oval and has an apparent size of almost 100 arc seconds, making it around twice as large as Jupiter. Its atmosphere is constantly expanding at 50 kilometres per second. This means that it grows by one arc second per century. The Ring Nebula’s real diameter is one light year across, and it is 2,300 light years from Earth.

You can find it with 15x70 or 20x80 large binoculars, but then it only appears as a point shape. Its delicate smoke ring can be seen beautifully through a telescope at a magnification of 100 times or more. If you observe closely, you will discover regions of varying brightness.

How do you find the Ring Nebula? It’s hidden in the small constellation Lyra, which can be found high in the sky in the summer months. The main star, Vega, appears as one of the first stars in the sky at twilight. Lyra forms a parallelogram with its main stars. The Ring Nebula is easily found between the two lower stars Gamma Lyrae and Beta Lyrae.

Locating chart for the Ring Nebula, Stellarium

Locating chart for the Ring Nebula, Stellarium3. NGC 7662 - the snowball in space

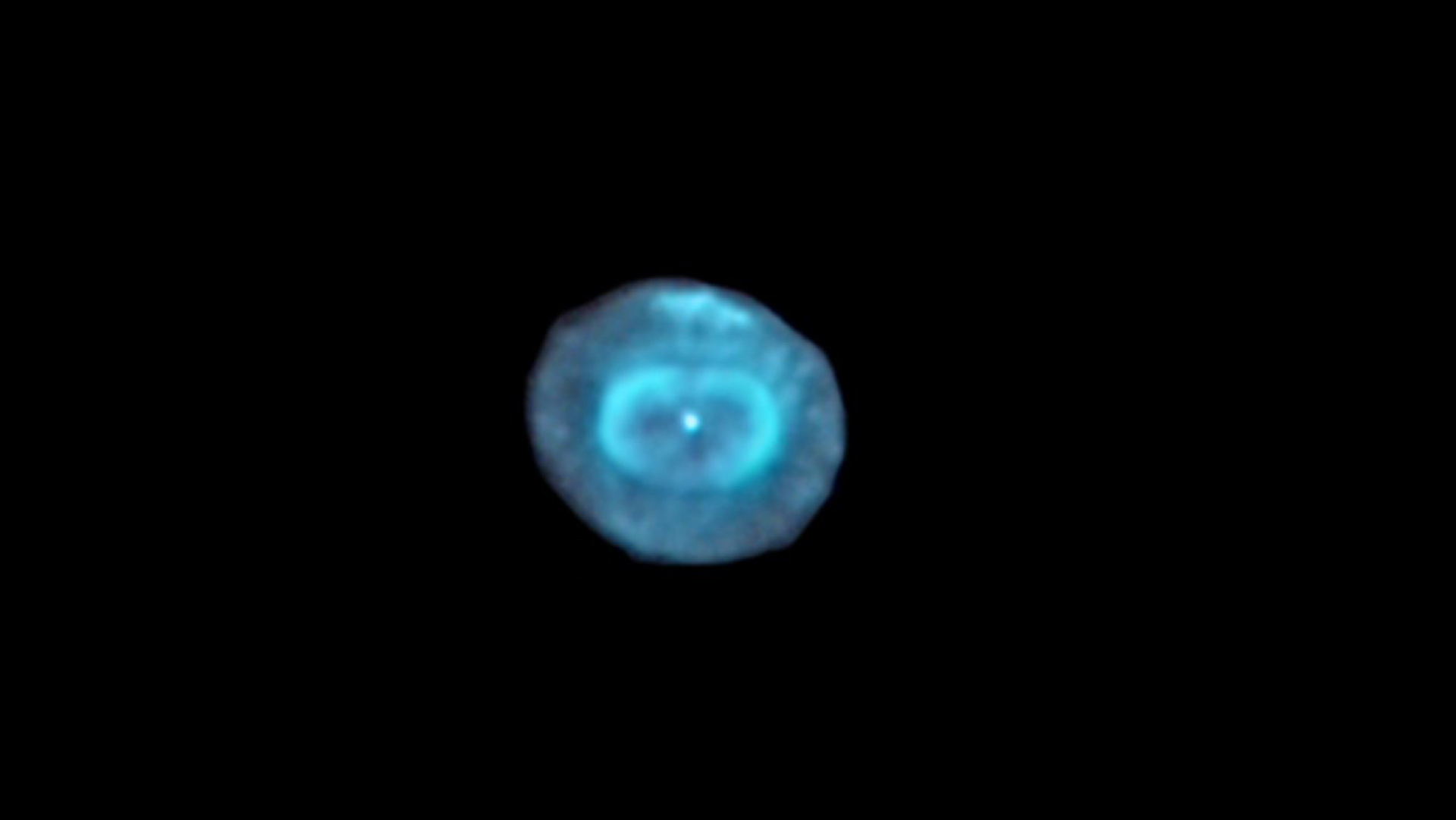

The Blue Snowball is a beautiful planetary nebula of the autumn sky, with a visual brightness of mag 8.3. Its clear blue colour, which also gave it its name, can be seen through telescopes of all sizes.

William Herschel discovered it in 1784 and described it as a planet-like disk with a diameter of 15". One can very well imagine how astronomers of the time could confuse such a nebula with a planet like Neptune - not least because of its colour.

NGC 7662 - Blue Snowball, photo: Bernd Gährken

NGC 7662 - Blue Snowball, photo: Bernd GährkenThe Blue Snowball, which is 6,000 light years away, appears so blue to us because it emits light in the OIII lines of the spectrum at 500 and 495 nm, which we perceive as a blue-green colour. In its centre is a very hot white dwarf with a surface temperature of 75,000 Kelvin. Unfortunately, we cannot see the central star even with the largest amateur telescopes. One reason could be that the nebula appears too diffuse even in the centre, and so the central star has no chance to shine through it.

Even through binoculars or through a telescope with low magnification, we can see a blue point, that cannot be distinguished from a star. This makes it difficult to recognise it at first if you cannot correctly locate it. It is to be found in the company of several bright stars.

At a slightly higher magnification of 30 times, we can see a small disk that does not appear round, but rather oval. Now we also notice its diffuse appearance, which is clearly different to that of a star. Because of its high surface brightness, we can easily increase the magnification to 150 to 200 times and make out a bright outer area and a somewhat darker inner section.

How do we find the Blue Snowball?

NGC 7662 is located in an area that has relatively few bright stars. The bright main stars of the neighbouring constellations are a good 10°-15° distant. Halfway from the binary star Alpha Andromedae, in the direction of constellation Cepheus, you will find a chain of three stars that are mag 3.8 to 4.2 bright. Orient yourself with your finderscope pointing at the lower star, Iota Andromedae, and then move two degrees in a westerly direction.

Locating chart for the Blue Snowball, Stellarium

Locating chart for the Blue Snowball, Stellarium4. NGC 6826 - the blinking planetary nebula

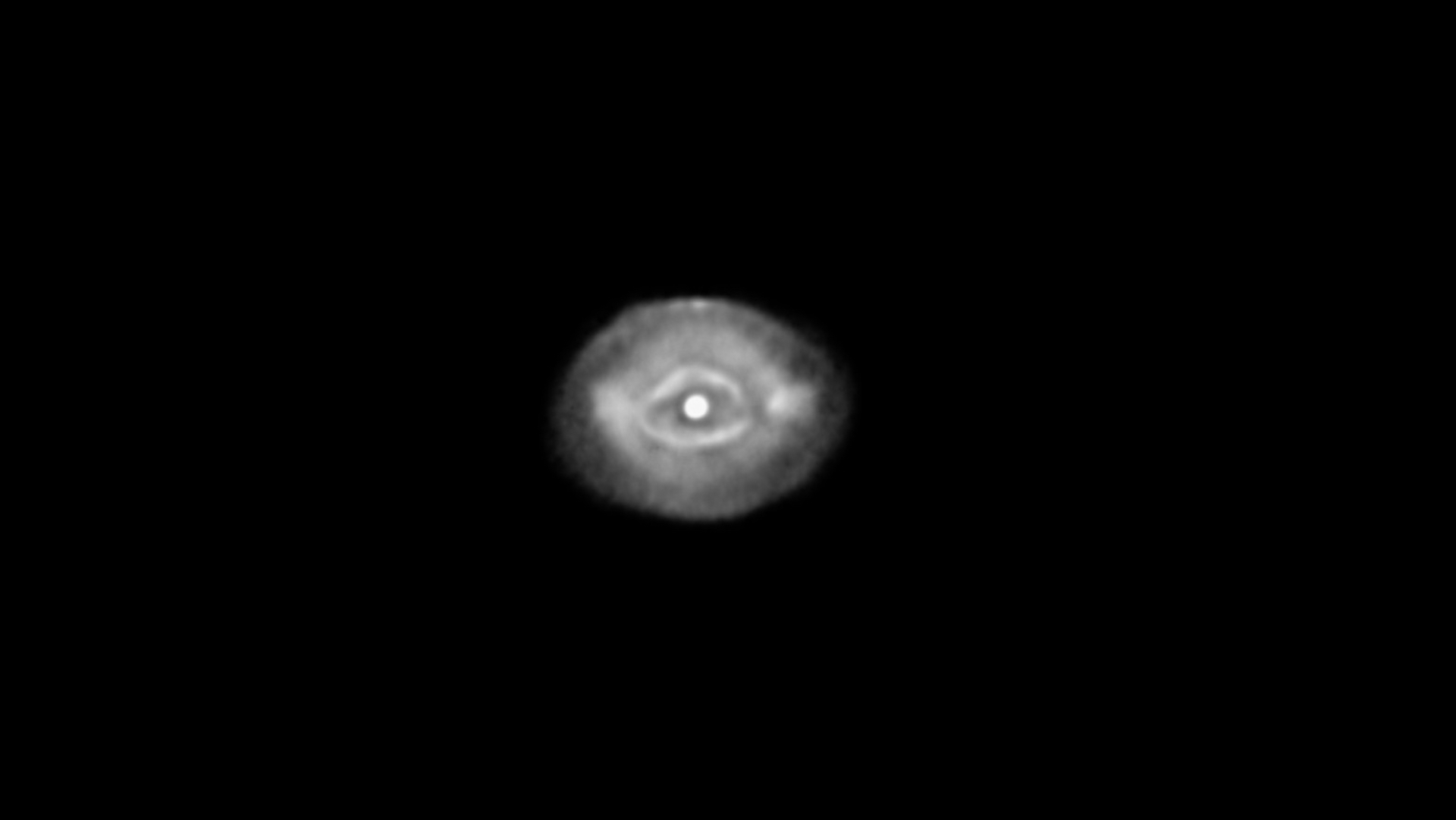

Among the objects in the sky, there are many curious companions, for example the Blinking Planetary nebula NGC 6826. Yes, you read it correctly: when we observe this nebula, it actually blinks.

How is this possible?

It is not an astrophysical effect, the explanation lies in the physiology of our eyes, in which the image alternately falls on sensitive and non-sensitive areas of the retina.

NGC 6826: Blinking Planetary, photo: Bernd Gährken

NGC 6826: Blinking Planetary, photo: Bernd GährkenYou can observe NGC 6826 even with a small telescope. Due to the effect, this is even more fascinating than with large telescopes. With a brightness of mag 8.8, you can find it relatively easily in constellation Cygnus. However, it is not so easy to recognise at first glance, because it appears extremely compact at small magnification and at first you only see the bright central star. So you need to know in advance where to find this "little star".

Once you’ve found it, switch to 100-times magnification, and you’ll immediately notice the mag 10.6 bright central star. But where did the nebula get to? It is compact and very round, but you won’t see it if you observe in the usual way. But if you look past the central star, the nebula appears like a ghost in the eyepiece. Let your view wander backwards and forwards, and it will start to blink, disappearing and reappearing.

You can only see this fascinating effect in smaller telescopes. It is created by the effects of direct vision (when we look directly at an object) and averted vision (when we look slightly to one side) and is only visible when the object is at the telescope’s detection threshold.

How do you find the nebula?

In the left wing of the Cygnus (or if you see the Cygnus as a cross, then on the right side) you will find the stars Delta Cyg and Iota Cyg, and between them the mag 4.4 bright star Theta Cyg. Move about 50', or just about one degree, towards a mag 6.2 star. From here it's another 24' to the Blinking Planetary nebula NGC 6826. If you use low magnification and an extreme wide angle eyepiece, you can see the nebula together with the chain of stars by aligning Theta Cyg at the edge of the field of view.

Locating chart for the Blinking Planetary nebula, Stellarium

Locating chart for the Blinking Planetary nebula, Stellarium5. M76 - the planetary dumbbell in the sky

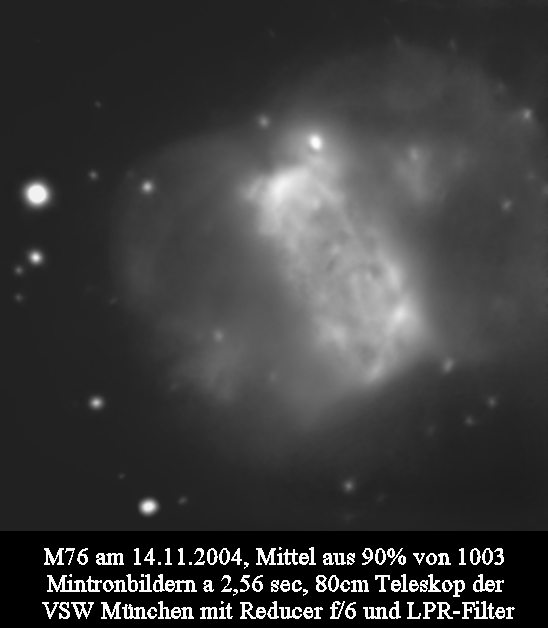

It is known as the Little Dumbbell Nebula, the Barbell Nebula or the Cork Nebula: M76 is one of the four planetary nebulae in the Messier catalogue. It's the faintest member, but it offers a simply lovely observation experience.

If you’re going to look for it with binoculars, you need to know exactly where you are looking and already have some astronomical observation experience. Nevertheless, you can easily observe it with somewhat larger 20x80 binoculars, through which you will see a tiny nebula speck. It is through a telescope, however, that it shows its true splendour.

What's the background to this object? It has a close binary central star of almost magnitude 18 and a surface temperature of 140,000 Kelvin. The nebula emanating from the stars is 2,500 light years away and is expanding at 50 kilometres per second or 180,000 kilometres per hour. As a comparison: the Voyager 2 spacecraft, which has been travelling through space since 1977, reaches 48,000 kilometres per hour, and has travelled 18 billion kilometres since its launch.

At very low magnification, M76 is almost star-like or round. Only at 50 to 60x magnification is its cork-like, elongated appearance revealed. With a 100-mm telescope, you can see a two-part structure with optimal magnification - it used to be thought that there were actually two nebulae. In a medium-sized telescope you can see two bright areas to the east and west, almost one structure, with a dark strip in the middle. With an OIII filter or UHC filter under dark skies, you can sometimes see two small arches that wind out of the nebula.

How do you find the nebula?

In autumn, M76 is high in the sky and is therefore also easy to see. Finding it is a little more difficult. We roughly orient ourselves to the constellations Cassiopeia and Andromeda: you will find the Little Dumbbell Nebula almost exactly in the middle between them. Nearby there are two medium-bright stars with mag 3.5 and 4.0. The first - Upsilon Andromedae - is the brighter one, from which you need to move a good 2 degrees further (toward Cassiopeia) to the second star - Phi Persei. Now it's not much further: only about 50' further, and you have reached your destination.

Locating chart for the Little Dumbbell Nebula, Stellarium

Locating chart for the Little Dumbbell Nebula, StellariumThe bottom line

These 5 planetary nebulae are among my favourites, and I can't get enough of them. You have the feeling that you're discovering something new every time you observe them. Which of these nebulae will you be observing during one of the coming nights?

Perhaps, while observing, you can imagine yourself back in Wilhelm Herschel's time and ask yourself what you are actually seeing.

I wish you lots of observing fun.

Author: Marcus Schenk

Marcus is a stargazer, content creator and book author. He has been helping people to find the right telescope since 2006, nowadays through his writing and his videos. His book "Mein Weg zu den Sternen für dummies Junior" advises young people, and those who are still young at heart, what they can discover in the sky.

As a coffee junkie, he would love to have his high-end espresso machine by his side under the starry sky.