Magnificent desolation

No target in the sky reveals as many details as our Moon. But what exactly is there to see? We give you a brief overview in this article.

Lunar seas, craters and mountains... the Moon features fantastic landscapes. Mario Weigand

Lunar seas, craters and mountains... the Moon features fantastic landscapes. Mario WeigandThe wide range of formations on the Moon

Because it interferes with light-sensitive deep sky observation, many amateur astronomers see the Moon as an irritation rather than an object to discover. But as the Earth's closest celestial body, the Moon offers an almost inexhaustible variety of lunar landscapes - especially for beginners.

Even with a small entry-level telescope, you can observe many of the magnificent craters, mountains, valleys and rilles that take on a variety of appearances depending on the available light. Besides, the Moon is visible for most of the month. Buzz Aldrin, the second human on the Moon after Neil Armstrong, described our satellite as "magnificent desolation."

Lunar maria

Your first visual encounter with the Moon requires only the naked eye, because the largest formations are easily recognisable: the lunar maria (Latin for seas). These dark-looking patches cover about 30% of the visible lunar surface. The maria are the craters created by giant meteorite impacts, which were flooded with magma that emerged from the punctured lunar crust. The colour is caused by the cooled rock: it is dark basalt lava. The largest structure of this type is the Mare Imbrium (Sea of Showers).

Crater upon crater

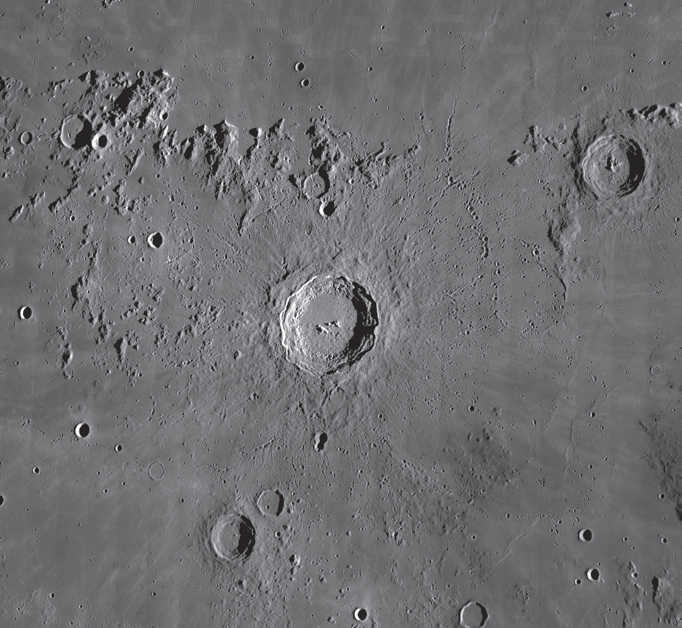

Copernicus is an example of a mountain ring. NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

Copernicus is an example of a mountain ring. NASA/GSFC/Arizona State UniversityA pair of binoculars or a small telescope is needed to observe the most common formation on the Moon: craters, which were also formed by meteorite impacts. On the near side, facing Earth, there are around 300,000 craters with a diameter of one kilometre or more.

They are divided into different classes according to size and condition: craters in the strict sense are around 5 to 60km across. They are mostly round in shape and stand out clearly against the background. The inner slopes are mostly smooth and there is no central peak. Small craters are no larger than around 5km. Mountain rings, on the other hand, have a diameter of around 20 to 100km and have well-preserved and clearly defined walls. Stepped terraced slopes in the interior of the crater are a typical feature. As a rule, the inner surface is dominated by a central peak. The best known example is Copernicus (see Adventures in Astronomy 1).

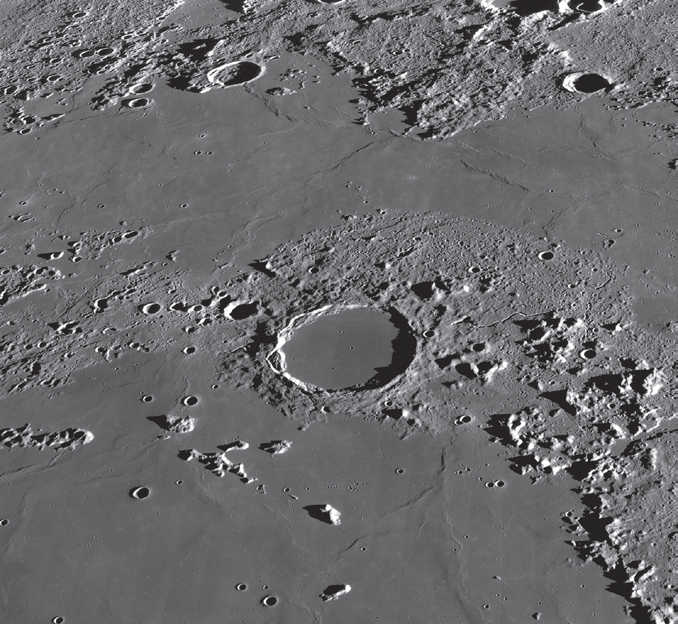

The even larger craters, with a diameter of up to 300km, are known as walled plains. These large craters are surrounded by a wall that has usually already disintegrated or was destroyed by later impacts. The crater floor is often broken with further craters, rilles and peaks and flooded with lava, such as crater Plato.

Mountains and valleys

The crater Plato is completely flooded with lava. NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

The crater Plato is completely flooded with lava. NASA/GSFC/Arizona State UniversityLunar mountain ranges (lat. Montes) are mainly to be found on the edges of maria. During the formation of the lunar maria, mighty crater walls several thousand metres tall are thrown up by the impact and later partly flooded by lava. The mountain ranges of today are the remains of these former crater walls. But unlike on Earth, they are much less rugged and more comparable to huge hills. The Montes Appenius is a particularly impressive example. Individual mountains (lat. Mons) are virtually always found in the lunar maria. They are also the remnants of crater walls, but here only the highest peaks can be seen towering above the lava-flooded plains.

Valleys (lat. Vallis) are divided into three types according to their differing origins. Crater valleys are linear structures created by overlapping impacts. These were probably caused by secondary impacts during the formation of the large maria. Linear crater valleys are the most common type of lunar valleys, Vallis Snellius is the longest valley of this kind. Volcanic valleys, on the other hand, e.g. Vallis Schröteri, have a sinuous shape and appear to the observer to be similar to terrestrial rivers. In fact, they are collapsed, former lava tubes. Graben are formed by the subsiding or collapsing of the underlying layers of rock. The most famous example is the Vallis Alpes.

Rilles and escarpments

The largest mountain range of the entire near side of the Moon are the Montes Appenius. NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

The largest mountain range of the entire near side of the Moon are the Montes Appenius. NASA/GSFC/Arizona State UniversityRilles (lat. Rima) are also grouped into different categories due to their different origins. Sinuous rilles, like volcanic valleys, are collapsed former lava channels. Straight rilles, on the other hand, have been caused by stresses from cooling lava. Escarpments (lat. Rupes) in lunar morphology describe a number of different features: scarps, slopes or cliffs. Essentially, there are two types of so-called escarpments: stepped terrain as a result of soil subsidence at the edges of maria such as the Rupes Recta (Straight Wall), and remnants of mountain rings or crater segments such as the Rupes Altai.

Author: Lambert Spix / Licence: Oculum Verlag GmbH