Four in one go

Through binoculars or a telescope: the changing constellations of the four bright moons of Jupiter offer a spectacle that never gets boring.

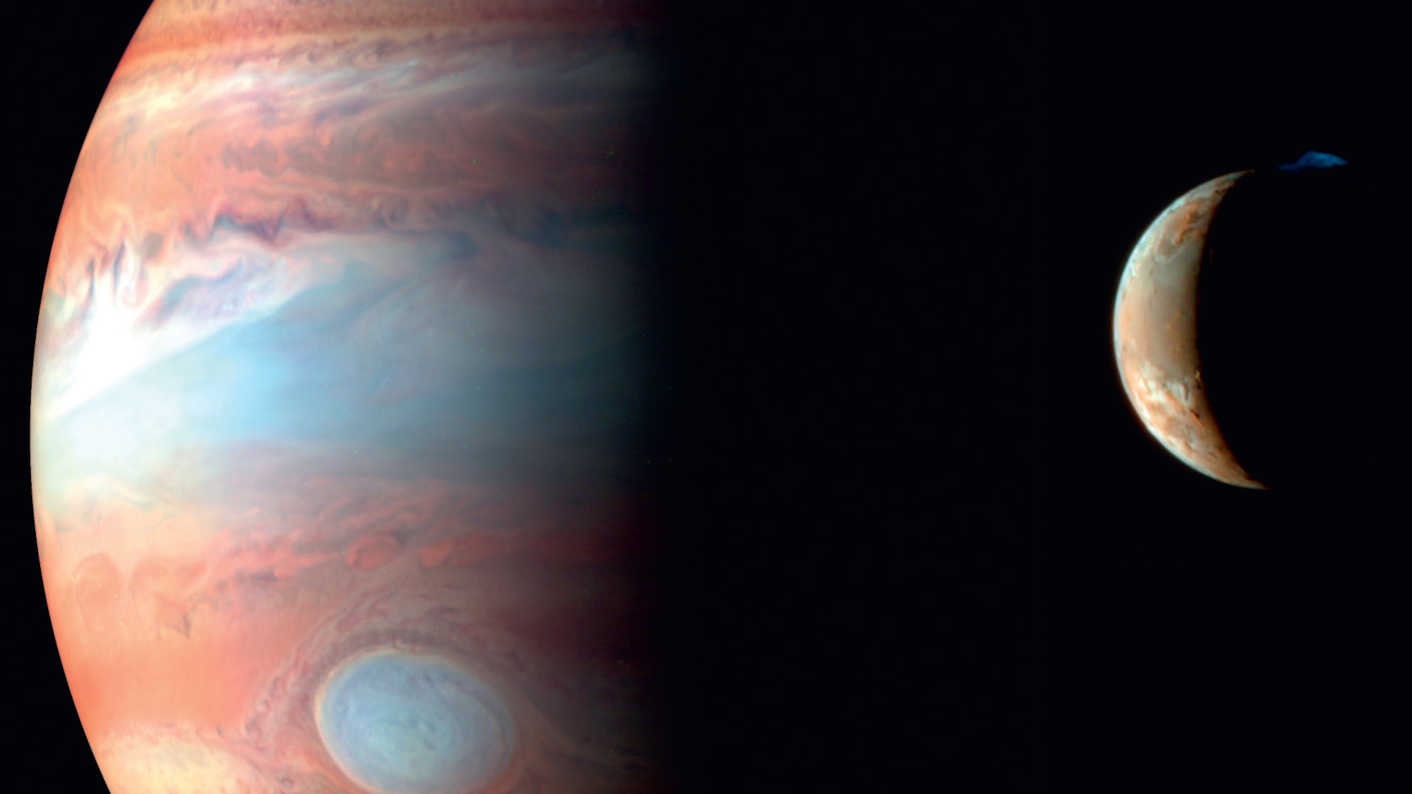

The innermost moon Io orbits the gas giant Jupiter from a distance of 421,600km. NASA/JPL-Caltech

The innermost moon Io orbits the gas giant Jupiter from a distance of 421,600km. NASA/JPL-CaltechObserving the moons of Jupiter

"On 7 January in this year of 1610, in the early hours of the following day, when I looked at the stars with a telescope, Jupiter showed itself to me; and because I had built a truly excellent instrument, I could saw three stars near the planet, small but very bright."

These words were written by none other than the famous Italian philosopher, mathematician, physicist and astronomer Galileo Galilei, who discovered the four brightest moons of Jupiter with this observation and, with it, was able to prove for the first time that there are celestial bodies that do not orbit the Earth. This confirmed Copernicus’ heliocentric world view, which was conceived some 100 years earlier, and which placed the Sun at the centre of the solar system. Today, these four moons are known as the Galilean Moons in honour of their discoverer. They are called Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

In the footsteps of Galilei

For amateur astronomers, observing the Galilean moons is a popular exercise, you only need a pair of good quality 8×30 binoculars to recreate Galilei’s observation from those times. Through binoculars, they appear as small points of light, very close to Jupiter. To do this, it is helpful to mount the binoculars on a tripod or, at the very least, steady yourself against a house wall. After a few hours, the positions of the moons change noticeably so it’s worth observing them frequently. Since we are viewing the moons’ orbital planes from the side, the satellites can also disappear in front of or behind Jupiter. So you can usually see all four of Jupiter's companions, but sometimes only two or three are visible. Take a look at a planetarium program in advance to ensure that you identify them correctly and don’t confuse the moons with stars. The free Stellarium program, for example, is useful for this.

The view through a telescope

In a small entry-level telescope with a 70mm aperture, the view is basically similar to that with binoculars: if the conditions are good, two bands of clouds are visible, Jupiter is clearly recognisable, and the moons can be seen as small points of light. A special treat, which is only visible with a telescope, is to observe the shadows cast by Jupiter's satellites. The moons pass in front of Jupiter in such a way that each satellite’s shadow is projected onto Jupiter’s cloud cover as a tiny, jet-black dot. The dates for these events can be found on the Internet, for example at www.calsky.com. If you have a telescope with an aperture of around 150mm or more, you can identify the moons as tiny discs and even distinguish their differing sizes.

In detail – a profile of Jupiter’s moons

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona, NASA/JPL/DLR, NASA/JPL, NASA/JPL/DLR

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona, NASA/JPL/DLR, NASA/JPL, NASA/JPL/DLRIo

The innermost moon Io is the most volcanically active celestial body in the solar system. Its surface has hardly any impact craters and is constantly changing. The most striking structures are hundreds of volcanic calderas and lakes of molten sulphur. Deposits of sulphur and sulphur compounds give the moon its strikingly colourful appearance. In contrast to the other Galilean moons, there is virtually no water on Io.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona, NASA/JPL/DLR, NASA/JPL, NASA/JPL/DLR

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona, NASA/JPL/DLR, NASA/JPL, NASA/JPL/DLREuropa

Jupiter's second innermost satellite is an icy moon. Its crust consists entirely of frozen water and it has one of the brightest surfaces of all the moons of the solar system. The surface is relatively smooth and its structures are reminiscent of the Earth’s polar regions. It is thought that there could be an ocean of liquid water under this ice crust, giving rise to speculation about forms of life on Europa. However, there is no evidence to date.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona, NASA/JPL/DLR, NASA/JPL, NASA/JPL/DLR

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona, NASA/JPL/DLR, NASA/JPL, NASA/JPL/DLRGanymede

With a diameter of 5,268 km, the icy moon Ganymede is the largest moon in the solar system, larger than the planet Mercury. Its icy crust has many impact craters, similar to the Earth's Moon. A recent study has suggested that Ganymede could have a salt-water ocean under the ice crust.

Four moons of Jupiter with their different appearances. NASA/JPL/University of Arizona, NASA/JPL/DLR, NASA/JPL, NASA/JPL/DLR

Four moons of Jupiter with their different appearances. NASA/JPL/University of Arizona, NASA/JPL/DLR, NASA/JPL, NASA/JPL/DLRCallisto

The outermost moon of Jupiter also has an ice water surface which appears much darker than the other satellites. The surface is covered by a large number of impact craters. In fact, Callisto has the highest concentration of impact craters in the solar system. As with Europa and Ganymede, there is probably a salt water ocean under the surface.

Practical tip

Jupiter through a telescope with a 70mm aperture (simulation). Lambert Spix

Jupiter through a telescope with a 70mm aperture (simulation). Lambert SpixThe right magnification

A magnification range of 60× to 80× is sufficient for observing the moons’ shadows, you don’t need high magnification to observe these. This keeps the image sharp and high-contrast in the eyepiece. Very calm conditions are essential.

Author: Lambert Spix / Licence: Oculum Verlag GmbH